Good news everyone: My dissertation was just submitted and accepted for final approval! This means it just needs to get signed off by the university, so in a few weeks I will be an official Ph.D.

Part of the reason I started this blog was to communicate the results of my dissertation research to the public rather than let it become a relic left to collect dust on some library shelf, or an electronic file referenced by a small group of scholars. I wanted to share my research with the public and fellow researchers who don’t share my specialization.

The first few blogs of this series were meant to familiarize my readers with why studying food and pottery is important and how they can be used to study people of the past. So now I am FINALLY getting to the point: what is my research and why does it matter?

My research explores the ways in which ancient peoples interacted with their environment through food selection, culinary choices, and cooking technology. As I noted in my previous blogs, I investigate these issues through sites occupied by Native American group in the Upper Great Lakes of North America between AD 0-1600.

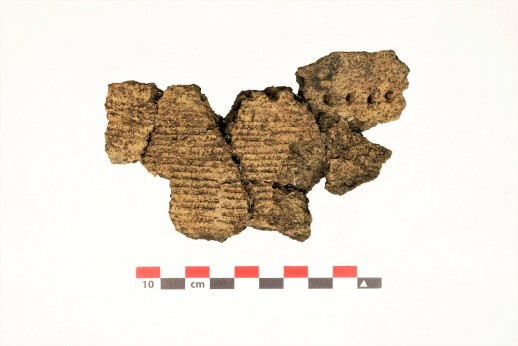

A beautiful Middle Woodland Laurel pottery vessel fragment from the Cloudman site (ca. AD 100)

Although pottery was used by groups living further south beginning around 1000 BC, many groups living along the shores of Lake Superior and northern shores of Lakes Michigan and Huron did not adopt pottery until 1000 years later. This was not because they didn’t know how – they traded and interacted with pottery-making groups and were certainly capable. They just simply didn’t need it and instead cooked over the fire or in vessels made of skin and birchbark. But at some point the use of pottery became advantageous and appealing enough for them to adopt and use it. And that’s lucky for me because, as I pointed out before, pottery is a treasure trove of information!

The pottery vessels made by precontact Native American groups were not painted, glazed, or slipped. Therefore, they are somewhat porous and when they are used for cooking, food particles can be absorbed into the walls of the pottery. The cooking pots were also used over the fire, which can make it hard to control the temperature, resulting in burned food encrustations on the inside of the pot. Skilled analysts (not me) can analyze the chemical signatures of both absorbed and adhered food remains. Burned food crust can also be analyzed for microscopic plants remains called phytoliths and starches, which are unique to individual plant species.

The Cloudman site and other important Woodland period sites in the Upper Great Lakes (image by S. Kooiman)

For my dissertation, I analyzed ancient pottery excavated from the Cloudman site on Drummond Island in Lake Huron, which was excavated in the early 1990s. The site was occupied by indigenous peoples from AD 100 until almost AD 1700, making it a great site to look at change through time. The pottery had been categorized by style (Branstner 1995) but never for function, so I looked at the physical properties and use-alteration traces of the pottery to determine their functions and cooking styles. I then collected some of that sweet, precious burned food residue from the pottery and sent them to specialists trained in lipid residue analysis, stable isotope analysis, and microbotanical analysis to determine what kinds of foods were cooked in the pots (I’ll provide an in-depth breakdown of these analyses in a future blog).

By understanding what was being cooked, as well as how it was cooked, we can begin to piece together ancient cuisine. Cuisine can help us interpret and understand identity, social interactions, and adaptations to climate and environment, and how these factors change, often in relation to one another, over time. This, in turn, can help us understand our own relationships with food traditions and our social and natural environments.

I hope you all stay tuned as I begin to share my results and interpretations, and please feel free to share your questions, thoughts, and insights with me, too!!

Reference

Branstner, Christine N.

1995 Archaeological Investigations at the Cloudman Site (20CH6): A Multicomponent

Native American Occupation on Drummond Island, Michigan, 1992 and 1994

Excavations. Report on file at the Consortium for Archaeological Research, Michigan

State University, East Lansing.

Thanls! I’m really enjoying this series!

LikeLike

I’m glad you like it!

LikeLike

Congratulations on submitting! I am looking forward to learning more about your work.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

I do a lot of cooking in pottery as part of medieval cooking research, and we rarely burn stuff. We cook over lump charcoal for safety reasons and because (after testing we found that) it reasonably emulates cooking over wood coals. Note: Lump charcoal, not briquette – the two are very different!

Burning is indeed a hazard, but can be avoided the majority of the time. (In my experience.) That leads me to wonder what the ratio of pots with burned residue to pots without is.

(Further caveat, our cooking circumstances are very different! They probably didn’t have had a dedicated fire tender.)

LikeLike

Hi Derek – thank you for your insight. There is a lot of burned food residue on procontact pottery from throughout the Great Lakes region. I think it’s related partly to the technology – cooking over open fires in ceramic vessels with little to no slip or surface treatments, making it hard to control temperature. I also think it’s a result of cuisine, or cooking culture. Women were the primary cooks in hunter-gatherer societies, and they were in charge of most food preparation and childcare, so it’s assumed that pots of food were often placed on the fire to stew foods for long periods of time, and they probably weren’t always closely attended. So you are right–you might not always be able to use burned food residues on pottery to interpret past diet for certain societies/time periods. Fats/lipids often cannot be extracted from vessels with surface treatments, either. So while these methods can be applied to a lot of pottery assemblages across the world, they may not be applicable to others.

I would be interested to hear more about your cooking experiments! I love to learn about cooking from all time periods and regions.

LikeLike

Pingback: Food for Thought: Odds and Ends | Hot for Pots